As I walked by the iconic church of Tangier and its tall bell tower shortly after I arrived from France, I was struck with how different it looked from the rest of Morocco. There was a tiny stone wall surrounding it, which separated the Muslims in the streets of Morocco from a small group of sub-Saharan Africans standing in front of the doors of the church. This scene seemed like a glitch in the Matrix, as if it had been displaced from another country — Nigeria, or Chad maybe. The men waiting there looked just as lost as me.

It was just like seeing the Great Mosque of Paris, a typically Moorish building, sticking out from the Haussmanian boulevards—a piece of Morocco in the middle of France, where you’d trade your café noir for a glass of mint tea and your croissants for a plate of various oriental pastries. The church contrasted with its surroundings, just like its faithful contrasted with the Moroccans.

It was also the first time I had found sub-Saharan Africans in Tangier. I knew they were there, waiting at the crossroads between two continents, looking across the borders to Ceuta or Gibraltar, longing for a better life. From the cliffs of the Kasbah, you can see Spain—Europe is barely out of reach. Tangier is the last stop before the final challenge, just before they reach their goal. But somehow, I felt they were hiding. From what? The law? From racism? From shame? I didn’t know, and it seemed like neither did anyone else.

I was determined to find those migrants, hear their stories and learn from them. And what better time and place to do so than my semester in Tangier? There was only one problem. Whether it was the shyness of the sub-Saharan migrants or my own shyness that stopped me from finding someone to talk to, I felt I needed help. I had thought of contacting someone who worked in an NGO, with migrants, as that is the career I am pursuing. But I heard about Father Dennis, a Nigerian pastor at the Anglican church of Tangier, who worked with and for the migrants and provided them with all kinds of help. Even better, I thought, and I set up a date and time for our interview.

On the day of the interview, I arrived at the large white church down the street from Iberia about half an hour early. A few people were waiting for something, scattered on the steps that led to the large wooden doors. I didn’t dare walk in past the gate, and I felt a little bit guilty about it. I had stereotypes, and they were holding me back: I didn’t want to be intrusive, I wanted to avoid getting in trouble—for whatever reason.

I was getting a few stares, and was growing increasingly uncomfortable until a young man walked to the gate and asked me in French:

“Are you lost?”

“Oh no,” I answered, “I’m just waiting to meet Father Dennis.”

He looked confused. I suddenly wondered if I was in the right place. I had assumed this was the right church, and I imagined that in a country like Morocco where 98.7% of the population is Muslim, there wouldn’t be too many churches.

Another man, whose body language failed to reassure me, approached me too. I looked around, hoping I’d find someone who looked like a pastor. No such person in sight. The weird man invited me in.

“Come with me to the basement,” he said, “we’ll find Father Dennis”.

“Uh, no, I think I’ll wait here.”

I was panicking, and the people around me looked confused:

“We don’t have a Father Dennis here. Maybe he’s in the other church.”

“The other church?”

“Yes, the Anglican Church. This is the Spanish Cathedral.”

“Oh, maybe.”

They called over another man, who supposedly went to the Church of St Andrews, where I would find Father Dennis. He offered to take me there, and I accepted.

His name was Adonis, and, like many of the sub-Saharan Africans here in Tangier, he wanted to go to Europe. In Greek mythology, Adonis was the lover of the goddess Aphrodite, who died young, in a hunting accident. I couldn’t help but fear that my new friend Adonis might one day reach the same tragic fate, as he goes hunting for a better future on the other side of the Mediterranean.

We walked down the street that bordered the cemetery. It was somewhat like a freak show: three-legged cats hopping around, dozens of severed goat heads and cow legs piled up on the pavement, sparks flying out of the ironworker’s shops as we walked by. It was as chaotic as Tangier gets, and Adonis barely even flinched.

He was a francophone Cameroonian, born in an anglophone region of Cameroom—which was, as I knew, not an easy life to begin with—the rise of insurgents seeking independence brought a surge of violence and killings to the western regions of the country.

“Is that why you left ?” I asked

“No,” he says, “I left because of Boko Haram.”

I nodded. That sounds similar, I thought, thinking of my Afghani friends back in France, who had fled their homes because of the Taliban. Boko Haram was, just like the Taliban, a group of Islamist terrorists. Their name, originated from the local language, Hausa, could be translated to “Western education is forbidden” and reflects what they enforce: voting, wearing “western” clothing, receiving a secular education—are all considered “haram,” and anyone taking part in such activities becomes the target of Boko Haram’s violence.

Adonis was wearing a shirt and some jeans and talked to me switching between perfect French and English—I had no doubt that he was one of those targets.

“And if I’m not mistaken,” I told him, “the violence isn’t the only problem: they extort you, take your money, your land, your home, and if you do manage to survive the killings, you’re only left to starve.”

It wasn’t the most impartial thing to say, but Adonis turned to me as if I had just said something he had been waiting for someone to say for years:

“Exactly !”

He went on to explain his life here in Tangier. He’d been here for two years, had tried to cross to Europe five times already, and had been arrested five times. He couldn’t get a flat, or a job, because he was here illegally—he’d sleep at his brother’s house, near the Kasbah, and leave every morning very early to come to church. Not that he was fervently religious, it wasn’t even the “right” church — although he was an Anglican, he’d spend his time with the charities at the Catholic Spanish cathedral. They’d give him food, money, but, most importantly, security.

“The police are searching for us, they come to our houses every morning and try to take us away from Tangier. Every morning I go to church so they can’t catch me,” he said.

I asked why his brother had a house, and he didn’t.

“To be able to stay in Morocco,” he answered, “you need a carte de séjour. You only get this residency card after you’ve been here for five years, or if you get married to a Moroccan or a white woman.”

He paused, looked at me, and asked, “Are you married?”

I quickly pulled up my left hand and waved it in front of him, so he’d see my ring.

“I’m engaged,” I answered.

It was a lie, of course—had gotten the ring from my grandfather for my 20th birthday, and I only wore it on my ring finger when I was walking around alone in Tangier, so I could use it as a quick excuse to refuse any advances from strange men.

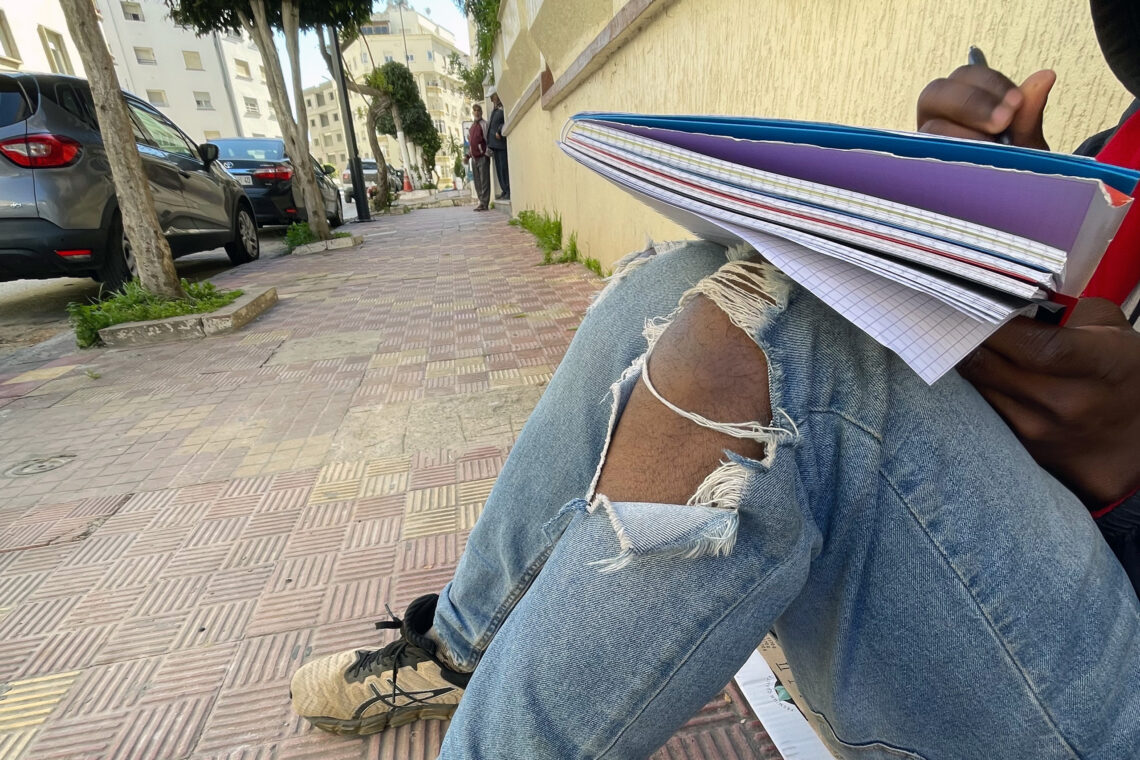

We finally arrived at St Andrew’s Church, and we sat on a bench in the cemetery while waiting for Father Dennis to arrive. Adonis continued:

“When you, as a black man, walk around Tangier with a white woman, it feels so much better — people look up to you, not down. Not that Moroccans are racist, though—the main problem is the police. When you’re with a white woman, people see you and think ‘Oh, they’re married that guy is allowed to be here.’”

I felt like the Aphrodite of Adonis’ story—a goddess of beauty, whose most interesting feature was her passport. I stopped asking questions, hoping the conversation would die down, or that Father Dennis would show up soon.

After another fifteen minutes of waiting, a tall, imposing, dark-skinned man, dressed in warm clothes and a ski cap arrived in the church’s courtyard. I wondered for a second who this man was until he was introduced to me as Father Dennis. After a quick chat, Father Dennis and I walked into the church. The pastor walked off to make some preparations, and I just paced around the small building, looking for curiosities.

The churches I was used to back in France were imposing, medieval buildings, made out of thick stone—architectural wonders that sheltered you from the outside world and whose structure seemed to be made to bring you closer to God. I get why people believe in God, I’d often think to myself when listening to prayers given in the Cathedral of Notre-Dame-de-Paris. Tangier’s Church of St Andrew was nothing like it. It was a small cement building that did nothing to shelter you from the chaos in the streets: the birds singing, the motorbikes’ engines revving, the locals at the nearby market yelling—I could hear it all. Most of the church was just benches. No fancy chapels on the side, no intricate paintings, and no valuable statues. Just a modest piano at the back, and old cushions on the floor.

Father Dennis then came back and sat on a bench in a corner at the back of the church. He silently started to read the Bible, and I awkwardly sat next to him for a while, not knowing how or when to start my interview. He finally looked up and gave me a slight smile, which I took as a sign that we could start. The first question was the usual “tell me about you” that was supposed to get a quick summary of his background—where he came from, why he chose to be a pastor, and why he came to Tangier. Easy, I said to myself. But oh, was I wrong.

I learned about his background from a small farming village in Nigeria; how he sowed his wild oats as a young man; and how after living a life of both freedom and sin, Dennis stopped drinking, got married, and tried to find God. Around 1994, as a thirty-five-year-old, he started going to church. A bishop from Ghana eventually asked Dennis to enter the seminary and become a pastor—an idea that had never crossed his mind. He had no background in religion and hadn’t lived his life as a future pastor would have been expected to. Father Dennis arrived in Tangier last year.

After furiously scribbling away on my notebook, trying to catch every detail of this unpredictable story, I asked Father Dennis about the sub-Saharan migrants.

“These migrants here,” he said looking me straight in the eye, “they are desperate. It’s difficult to tell them about God. They don’t want God—all they want is to go to Europe.”

Working for those migrants wasn’t easy, he said, because what they wanted, he didn’t have; what he had, they didn’t want. What they came for was money, food, or to meet a lonely white woman that they could marry for a residency card and a pass to Europe. Father Dennis didn’t have any money for them and couldn’t afford to feed them all every day—and organizing speed dating between migrants and European expats wasn’t the kind of activity you should expect of a pastor anyway.

I was surprised by the slight anger and frustration in his voice. He didn’t really sound like a pastor at this point. He took off his ski cap, but was still wearing his winter jacket, and I could only barely see his clerical collar peeking out at the base of his neck.

Our discussion was cut short by some racket coming from the church door. It opened and slammed shut. I noticed a small dark face peeking into the church.

“If you’re looking for me, I’m still outside,” said Adonis.

Father Dennis stared at Adonis. The young man disappeared without a word, slamming the heavy door of the church. Father Dennis turned to me. I finally got to ask the second question on my list:

“What’s a verse of the Bible that you particularly like? One that helps you in this situation, with the migrants?”

He grabbed a Bible sitting on his right-hand side, and slowly flipped the pages, searching for the verse he wanted, John 15:5:

“I am the vine; you are the branches. If you remain in me and I in you, you will bear much fruit; apart from me you can do nothing,” he recited, before continuing: “I read this verse when I wonder, ‘Is there anything too hard for me to do?’ Without God, you can’t do anything; but with the help of the Lord, the impossible will bow. And now I see the level of hostility in migrants dropping sharply. Some of them have jobs now, even though they have no papers.”

He smiled with pride and went on to tell me the story of his greatest achievement. He met one young man who came to his church: like many, he had come to Tangier to go to Europe. He had paid a smuggler for him to take him there and was told to wait three days. But these three days turned into three months, and the young man realized the smuggler had swindled him and run away with the money. He was now stranded in Tangier, and therefore like many, he had come to St. Andrews looking for food, money, or any kind of help Father Dennis had to offer. When the pastor’s wife approached him, she found out that the young man was, in fact, a Senegalese Muslim. But over time, he would spend more and more time at the church, listening to the sermons and the special prayers for the migrants.

Just like Father Dennis gets to know his faithful, he learned about this young man. He found out what were his strengths, his weaknesses, his background, and his goals. Father Dennis, his eyes gleaming with wonder, explained how the young man changed.

“I taught him to believe in himself, and he managed to find a job. He now works as an apprentice in a mechanic’s shop—with good pay, especially for a young man like him.”

“And here, God is just picking them one by one.” By this, I assumed he meant that the Muslim man was on his path to salvation.

I had heard that the previous pastor of the Church of St Andrews had set up a football team to get his faithful to stay in Tangier, by giving them a purpose here in Morocco—but despite the efforts, every other week, one of the players wouldn’t show up, and would wash up dead a few days later on Achakar Beach.

Father Dennis’ strategy was similar, in the sense that he wanted to give the sub-Saharan migrants a purpose on the African continent. Just like God had given the young, sinful, hard-drinking Dennis Obidiegwu a purpose as a pastor in the north of Morocco, God had a purpose and a plan for each and every migrant who ran aground in Tangier.

“My role is to help them to have the knowledge, about who they are and where they are going. I’m trying to teach a man to fish,” he said, “and it seems like it’s working. When I first arrived, the young men wouldn’t come to our prayers, because they were running around somewhere; and now, those who don’t come, don’t come because they’re busy working. I can forgive them that.”

I walked out of the church, feeling relieved that the interview was over and that Adonis wasn’t waiting for me outside. It was around 1:00 PM when I got out of the interview, and the market was buzzing with activity. I reflected on what Father Dennis and Adonis had both said or shown me. The original reason why I set out on this quest to find the sub-Saharan Africans of Tangier, and those who took care of them, was so that I could learn what I could do in my future career to help people in the same situation. What I’ve learned can be summed up in Father Dennis’ words:

“Give a man a fish and he’ll eat for a day, teach a man to fish and he’ll eat for a lifetime.”

Father Dennis has been doing admirable work. He finds young men and women stranded in Tangier, who are crippled by the successions of tragedies throughout their lives and their journeys to Europe. He fishes them out even before they set out on the sea and drown. He helps them gain hope again so they still can succeed on the African continent. And although you’d expect of a pastor to teach his faithful to believe in God, he teaches them first and foremost to believe in themselves. And thanks to him, the young migrants, who had thought there was no future outside of Europe, learn to use their past experiences to make a living here in Tangier.

Just like Father Dennis once did.

Comments are moderated by the editor and may not appear on this discussion until they have been reviewed and deemed appropriate for posting. All information collected is handled in a manner consistent with our privacy policy.