Walking out from the Ibn Battouta International Airport of Tangier, trying to drag two suitcases with a purse on my shoulder, I felt the warm breeze on my face and a strange sense of déjà vu. On the way from the airport to the UNE campus, I looked out the window and noticed rows of apartment buildings similar to the ones in Phnom Penh, my hometown. What caught my attention was the way people drove as well as the riot of cars, mopeds, and bikes on the road. I was in Tangier for a couple of hours and already felt like I belonged here.

Standing at the front gate of campus, all I could hear were the “wows” from the 31 students who came here on this journey with me. One student shouted, “This place is a palace.” I nodded at him and walked inside. Karima, the campus chef, had prepared lunch for us. I didn’t want to eat right away, so I went up to my room. The views from my bedroom onto the grass and trees reminded me, if only by virtue of the extreme contrast, of the parking lot I stared at from my dorm room in Maine.

After lunch, Douaa, the campus coordinator, didn’t want anyone to sleep so we went on a walk past Cafe De Paris to the Lazy Wall, a landmark in the middle of town which got its name because it’s a place for people to sit around and talk. I heard different languages being spoken, including Arabic, French, and Spanish. Being bilingual, I loved the cosmopolitan atmosphere. The intoxicating air smelled of car exhaust, burning cigarettes, and freshly brewed coffee. Men sat in cafes and watched soccer on TV.

From the Lazy Wall, I looked out to the Mediterranean toward Spain. I then turned and looked around me, and I didn’t see any other Asians on the street. Even if I was probably the only Cambodian in Tangier at the moment, I began to question why I felt like I was back home in Phnom Penh. Would the locals also remind me of my friends and family? To discover this, I clearly had to meet some Moroccans.

On one Saturday night, I thought I found my Moroccan muse when I went to a bar called the Tangerinn. I was sitting with some of my new UNE friends and I noticed this guy next to me. He waved his arms, threw back his head in laughter, and winked at me. Intrigued, I sidled up to him to say hi. He introduced himself as Othman and told me he’s from Rabat but goes to college in Tangier. We talked for a while before he asked a puzzling question.

“Do you have any cute friends?”

“Yes, I do.”

“Boys only! I like boys,” he said with a grin.

Coming to Muslim Tangier, I didn’t expect to meet a gay man. But I quickly concluded that Othman manages in Morocco the same way his counterparts do in Cambodia, a conservative Buddhist country. They violate the rules of religion but somehow still manage to be happy within society.

The conversation shifted, and we began to talk about fortune tellers. Othman told me he would go see a fortune teller once in a while to catch a glimpse of his future. I was fascinated by how open he was. I felt comfortable enough to ask him questions about the presence sorcery—a common practice back home in Cambodia—in Tangier, but he didn’t seem to know a lot about it. What he could say, though, was that people here believe in witchcraft and the evil eye.

This made me even more curious about this city. Back in Cambodia, magic is popular among most people. I’ve witnessed a ceremony where the monks performed a ritual to cast out evil spirits. My quest into the inner life of Tangier expanded to include abracadabra and compare it to Cambodia.

A few days later, I turned to the UNE campus manager Mourad, the man who knows everything about Tangier. I told him about my quest and without hesitation he told me to follow him. Mourad walked me to his office and pulled out one of the magazines on his shelf.

“Read about El Gourd before you go meet him.”

“Meet him?”

“Yes, he’s the guy you want to talk to about these things.”

I gave him a hug and thanked him. I took the magazine from his hand and started flipping through the pages. Abdellah El Gourd, I learned, was born in 1947 in the kasbah of Tangier, and he is a master of Gnawa music, whose rhythms and other healing properties can help people with psychic disorders—or demons. Gourd has performed around the world with Randy Weston, an American jazz pianist.

Mourad told me that one of the important rituals Gourd performs is the “Lila derdeba,” which means “night of trance” and is a lavish ceremony of song, music, dance, costume, and incense that takes place throughout the entire night, ending around dawn. The goal of the Lila is to heal the sick through chanting, dancing, and singing, which to my ears sounded like rituals in Cambodia. Mourad told me if I was lucky enough, I might be able to see the performance in person.

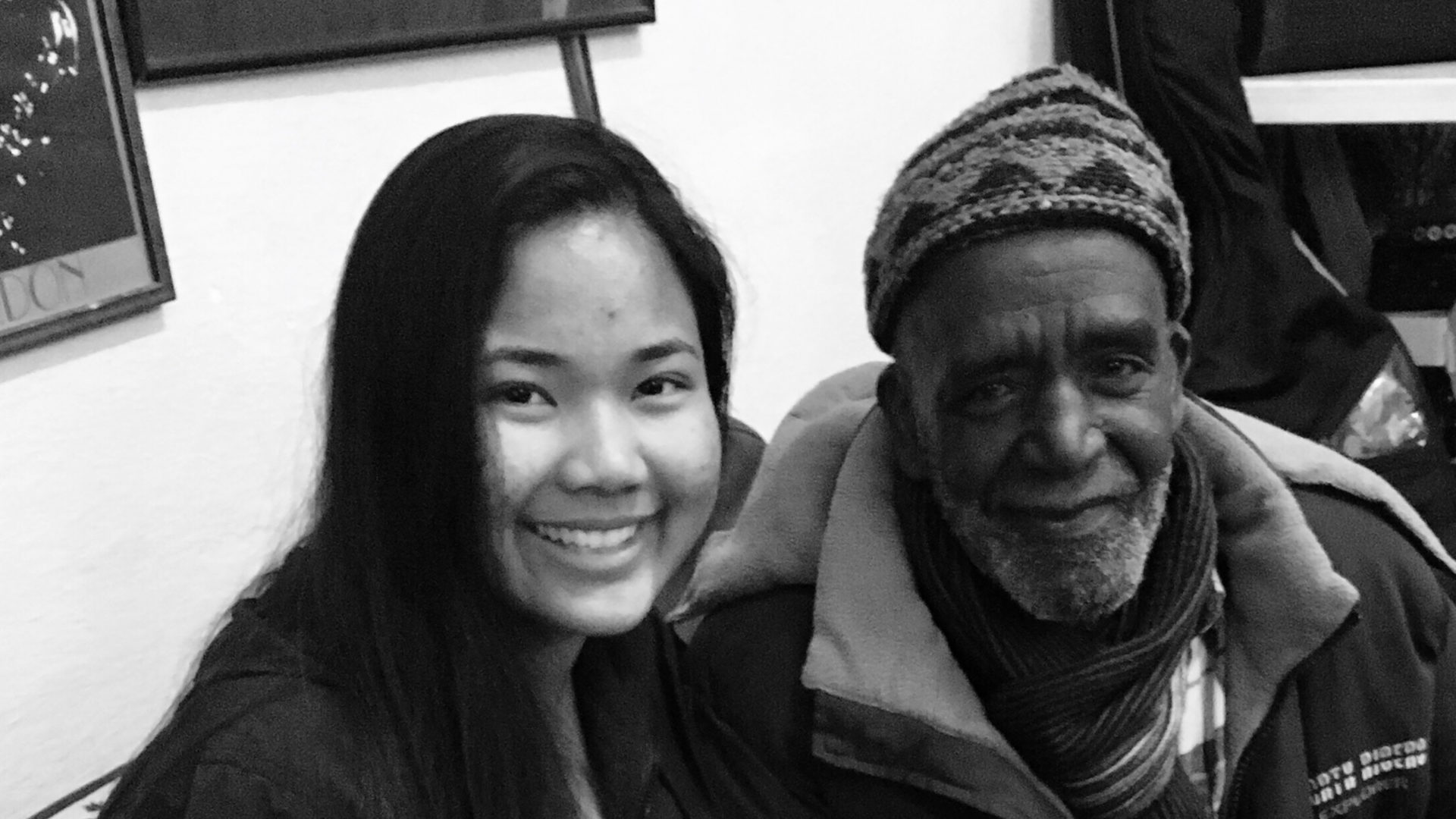

A couple of days later, around 6 pm, I walked to Gourd’s studio with Mourad. Mourad led the way through the Medina. We turned a corner, and Gourd was standing outside of his studio holding a cigarette.

“Salam Aleikum,” I said to Gourd.

“Waleikum salaam,” he replied with a chuckle.

I gave him a hug with a kiss on each cheek. As I entered his studio, I noticed pictures on both sides of the wall, including several of him with Randy Weston. I took a look around and felt my skin tingle from the energy of walking on sacred ground.

Gourd motioned me to sit down. I started the conversation by introducing myself to him, and I told him about my quest to learn more about the relationship between mysticism and Gnawa music.

“Welcome! I’m a lover of Gnawa. I’ve been playing since I was a small boy. My parents were Gnawi and I learned from them to become the master of Gnawa.”

“Is this the studio where you do all of your performances?”

“Yes, I do everything here.”

“Do you write your own music?”

“I do. I want to have music in written form for the next generation because in the past there was no written form of Gnawa, only oral.”

“What do you mean by oral?”

Gourd took a sip of his coffee then switched his position so that he was facing me.

“Let me tell you a little bit about my background. Before I became the master of Gnawa, I went on a quest to the Sahara to find the origin of my ancestors. When I came back, I started writing my own Gnawa music, so that I can let the future generation continue this legacy.”

I could see a passion but also melancholy in his eyes as he leaned over to grab his coffee.

“What is the purpose of Gnawa music?” I asked.

“It’s an opportunity for me to help others through music. I perform Lila here too.”

“Ahh, Lila, I’ve heard about it. Can you explain more about Lila?”

“Lila is a big ceremony every year before Ramadan.”

“And what’s the purpose of it?”

“It is a way to cleanse the body, mind, and spirit.”

“I heard you are the master of Lila. During the ceremony, do you feel an outside spirit join you?”

He looked at me with confusion, so I tried to explain. Something must have clicked, because suddenly he scrolled open his eyes and said, “You know, everywhere you go, no matter which country you are in, there’s always a spirit—the same spirit—from the outside. What matters is whether you believe in it or not. And performing the Lila, it’s not an easy process that you can just jump into it. You have to work your way up to it along with the music, and not everyone can do it.”

In my mind’s eye, I saw the Buddhist monks performing their magic.

“Have you done any rituals with casting out the evil spirit?” I asked.

Gourd looked like a man uncertain how much of his secret he should reveal.

“Like I said,” he cautiously began, “you have to believe in the spirit in order to see. Evil spirits are everywhere, and so are the good ones.”

I was trying to dig deep and ask him about casting out demons using Gnawa music, but he kept changing the subject and gave me different answers, as if he was keeping the secret from me.

But I was determined: “Have you used Gnawa to cast out demons?”

“Demons?” he laughed.

“I don’t know how it is with the culture here,” I tried to explain, “but in Cambodia, there are people who still use black magic such as putting a spell to make someone sick or use the spell to call out to the devil. So, I’m wondering if you use Gnawa to do the same?”

“Gnawa is a savior,” he said, lowering his voice. “I use it to help people in need.”

I sensed there was much more he could say but chose not to. He then switched the topic to talk about doing jazz with Randy Weston.

When I tried to return to the subject of magic, he told me I was “very curious.”

I smiled at him. “I like to be because that’s how I learn.”

He finished the rest of his coffee and put the cup on the ground. He turned back to me and said, “Whatever you do, don’t forget about your origins and your roots.”

I wasn’t sure how to respond to that, so I just assured him I wouldn’t.

He stood up and gave me the sign that it was time for him to go, so I thanked him for his time. I wandered around his studio for a little more before I left.

On the way back to campus, I couldn’t stop thinking about his words, “Whatever you do, don’t forget about your origins.” It was then that I realized he taught me a far more important lesson than the secrets of magic. It doesn’t matter where I go in life or what country I’m in, I must never forget about my Cambodian roots. I can be across the world and still make that new place feel like my old home because I remember who I am. It was not Tangier that made me feel like home, it was me this whole time. I was the one who made Tangier become my new home.

Comments are moderated by the editor and may not appear on this discussion until they have been reviewed and deemed appropriate for posting. All information collected is handled in a manner consistent with our privacy policy.