“You know that’s a Muslim country, right?” This was my mother’s reaction the first time I told her of my plans to spend a semester in Tangier, Morocco. After weeks of arguing back and forth about my safety, she conceded that I wasn’t about to pass up this amazing opportunity. I had made my decision, and I was going. “Just don’t tell anyone you’re Jewish” was her final comment.

My mother grew up in Russia where the practice of Judaism was looked down upon. There was only one synagogue in all of Moscow, and I remember her telling me stories of times she faced prejudices there. In the school grade book, the teacher would have each student’s nationality and religion next to their name. The teacher once told my mom that there were no seats left on the bus for their class field trip to the Red Square when there were actually plenty of open seats. When they tried to leave Russia to escape religious oppression, they faced many more struggles. It made sense why my mom would tell me not to tell people I’m Jewish since she was raised with anti-Semitism.

With my Jewish mother and Catholic father, I and my siblings were raised unreligious. When my parents got divorced it was decided that we would be raised Jewish, but that decision ended as soon as my dad chose not to drive us to Sunday school on his weekends and my mom didn’t feel like picking us up for it. I was only three years old and my religious life had already ended. Growing up I didn’t know any better. I was never taught about religion in school or at home, not many of my friends were extremely religious, and it just wasn’t something people normally talked about around me. I remember watching my stepbrother and sister at their bar and bat mitzvahs and my cousins at their communions and confirmations, but I never thought to ask any questions. At one point I tried asking my mom, but she was just as clueless as me. She came to America when she was 16 and was too focused on learning English and helping support the family to attend Sunday school.

Oddly, once I arrived in Tangier, being so blind to religion made me even more intrigued to see what this new country could teach me. A bit of research taught me that Jews. Christians, Bahais, and Jews have coexisted peacefully for centuries. In fact, Jews have resided here since the ancient Romans; more arrived in 1492 when the King of Spain ordered the expulsion of practicing Jews from his Catholic kingdom. Could it be, I asked myself, that here, in a Muslim country, I might discover my long-lost Judaism? How is this Muslim country so different than what my mom experienced growing up in Moscow? In Moscow when my mother was young, Jews were afraid to practice their faith, but here in Morocco they’ve lived in peace. Why?

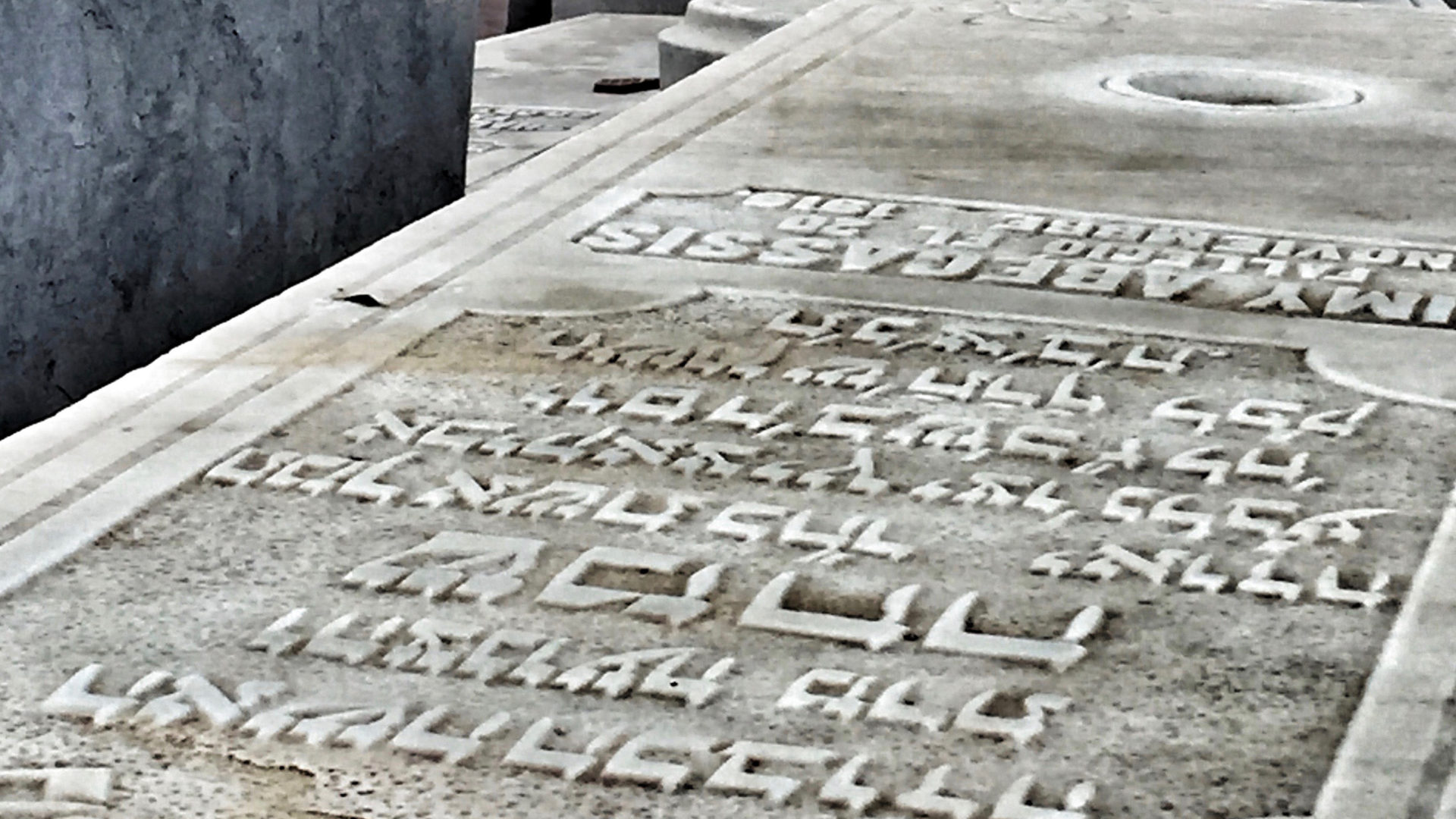

Our visit to Tetouan reinforced what I was learning; this country is not prejudiced against Jewish people. Many streets had Jewish names, and I learned that the city had been home to the largest Jewish community of Spanish Morocco. The Jews of Tetouan arrived in the late 15th and early 16th centuries. They helped spread Andalusian culture throughout the city. The Medina of Tetouan had been nicknamed “the little Jerusalem,” and the Jewish cemetery is located right in front of the Muslim cemetery.

Back in Tangier, I continued my quest. Now there are only thirty-four Jews left here and I couldn’t help but wonder why. What drew their ancestors here? What ended up driving them away after so many years?

I pondered these questions and began asking around. After many attempts to find a Moroccan Jew to guide me through their history, I finally heard about an older gay man named Mohammed reputed to know everything and everyone there is to know about this beautiful city, which is why he grew to know the Jewish community so well.

To meet Mohammed, I left La Fuga Cafe and headed towards the Grand Socco, hoping to quickly make it to his house by 10 o’clock. On the long walk, I thought of what I really wanted to know. Could a gay non-Jew, and apparently an atheist outsider to boot, give me the inside scoop about the Jewish community?

When I arrived, I shook his hand and introduced myself. The room was decorated with pastel colors, beautiful paintings lined the walls and fancy furniture pulled the room together. We quickly took a seat and I dove right into my first question; “Can you tell me about the Jewish community here?”

He began telling me about a famous Jewish musician who owned a night club by the shore, and about the Jewish woman in her 80’s who lived upstairs but only spoke Spanish.

I dug deeper and asked him about the history of the local Jews. “Judaism in Morocco is actually very ancient,” he said. “They started coming here in the 5th century BC, at the time of the Phoenicians.”

As I settled in and the conversation began to flow, I discovered that there is a difference between Moroccan Jews, who are regarded as Moroccan because they have been here for such a long time, and the Spanish Jews who came in waves, before and after 1492. These two communities don’t tend to mix well together because Moroccan Jews were mostly living in Berber areas and became Berber. The Andalusian Jews who came later are really much more open to civilization and science, so they moved to cities like Tangier, Tetouan, Fez, Casablanca, and Marrakech. I was excited to see that the Jewish community was more diverse than I had expected.

“And the Jews of Tangier?” I asked. “Is there something special about them?”

“There is one thing that set Jews here apart from other Moroccan cities,” he said. “There was no Mellah.”

“What is a Mellah?” I’d never heard the term.

“A Mellah is a walled Jewish quarter in a Moroccan city.”

Oh, I thought to myself. There was no ghetto like in Europe. Which got me back to my original quest: the differences between the Jewish experience in Tangier and what my mother experienced in Moscow. “Were there any problems between the Muslims and Jews in Tangier?” I asked.

He thought for a second before answering. “I don’t think at any point in Moroccan history Jews were targeted because they were Jews.” He explained that sometimes people would say that Jews were persecuted during the dynasties that controlled Morocco, but, in fact, everybody was persecuted. It wasn’t really like they were targeted.

After learning how Judaism ended up in Morocco and how they lived here peacefully, I continued to dig into why there aren’t many Jewish people left.

“I don’t think the Jewish community ever decided to up and leave. Moroccan Jews have always been Moroccan, which wasn’t the case in European countries. In Europe the Jews were regarded as members of a different nation—they weren’t Russian or German or Polish. That was never the case in Morocco. The Jews of Morocco were simply Moroccans; they were treated as Moroccan.”

I felt that I had learned everything there was to learn from this fellow outsider. I was interested in seeing what got him interested in learning about the Jewish community and learning about its history in Tangier. “What intrigues you about Tangier?” Since Mohammed is an atheist raised mostly in Holland, I was unsure of why he was so knowledgeable about the subject.

He said, “I look at everything. When you live in a city you want to learn about everything.” He was simply a curious man, intrigued by this beautiful city that seems to draw all sorts of people in to call it their home.

As I started on my walk back to campus, I noticed the Jewish cemetery off to my right. I started thinking about my own identity. Who am I? One thing for sure is that spending the semester in this multicultural religious place has opened my mind to religion. Not only am I learning a lot about my Jewish roots, but I will now be able to explain to my mom that being Jewish in Morocco can’t be compared to her experiences in Russia. I’d love for her to come and sit down with Mohammed. I’m sure they’d hit it off.

Comments are moderated by the editor and may not appear on this discussion until they have been reviewed and deemed appropriate for posting. All information collected is handled in a manner consistent with our privacy policy.