Doing this art project is going to kill me, I thought.

Mourad, our campus manager, led three of us girls down the street like a mother duck leading her ducklings, and I had no idea where we were going. It was hot, and the last thing I wanted to do was race to keep up with Mourad’s brisk pace while people stared at me limping along. We moved along the walkways of the Medina, past stray cats lounging in the light, as we traipsed from store to store looking for bandages for one of the girls. Not that I blamed the girls for needing a Band-Aid; I just felt like this was the worst time for Mourad to offer up his services. I didn’t want to show up late for the interview.

Mourad pushed me to walk faster. Continuing on, now winding down the old pathways of the city, questions crowded my mind. Where we were going? No one had told me anything about this place except that it was an art gallery in the Medina. Did the man I was scheduled to meet know any English? There was something else that confused me about this situation. I didn’t even know the man’s name. Did Mourad tell me and I forgot? Maybe Mourad didn’t know it.

I could feel the anxiety twisting up in my stomach, giving me the sensation of needing to throw up and cry at the same time. I had always struggled with anxiety, it’s been something that has crippled me as long as I can remember. But I couldn’t let my anxiety show that day. I just had to take a deep breath and ignore it, like always.

Mourad kept checking his phone, answering calls and stopping to shake people’s hands. I could see the sea in the distance and wondered how much longer the two of us would be walking. It was then that Mourad pointed a finger to a platform with cannons on it. We climbed stone steps and looked at the doorways. I still had no idea where I was, and I was starting to worry Mourad might feel the exact same way.

I had prepared many questions, such as how long this artist had been making art. Most people give me the typical “I’ve been drawing my whole life,” an answer I honestly hate. Everyone has been drawing for their whole life; children love to draw to express themselves. My question for the mystery man was when he got serious about his work.

My journey into the art world started sometime around high school. After years of sleeplessness, I finally got a chance to get more than four hours a night—and was quickly betrayed by the “solution.” Within ten minutes of taking the sleeping medication, I found myself on the floor, gasping for air while tears streamed down my cheeks. My mother came bursting into my room, scared from the clumsy text I sent. She sat on the floor next to me. I insisted that I was drowning; she insisted I wasn’t. Time passed—I can’t say how much—and soon enough I was knocked out for the night. I woke up to my mother on the phone the next morning. She was calling the doctor and telling them I had to go in; and once I was there, I found out something truly scary. My doctor told me that I had never been relaxed. The sensation of being relaxed was alien to my body, and because I wasn’t used to it, relaxation sent me into an alerted mode of pure panic.

Art has proven more reliable than pills. Art is something I can work with; it helps me express my interests or whatever might be wrong with me that day. I make art to calm down. It’s a sort of therapy. I still can’t get enough sleep, but it’s better than wallowing in a pit of anxiety all night.

Back in the Medina of Tangier with Mourad, a man came out of one of the doorways, gesturing for the two of us to come in. Flies flew in small circles in the center of the room. The walls that lined the place were covered in art, but it felt less like a gallery than the den of someone’s home. The mystery man moved his hands, pointing at the table where the flies had been hovering, beckoning us to sit down.

I relished the cool room, and the stress I had felt from walking was gone. But now I felt besieged by a different kind of anxiety. I don’t enjoy talking to people I don’t know; I’m like a little child who stands behind her parents, letting the adults do the jabbering. Mom always described me as shy, and relatives would always get mad that I wouldn’t pay attention to them but would stay close to my mother and watch the floor like it was the most interesting thing in the world.

I tried to focus on something that would keep me distracted while the man I was interviewing took a chair beside me, with Mourad sitting on the other side. Another man stood across from the table with paint splattered on his clothes; he was watching me. I had no idea who he was, but my guess was that he worked there. I could feel the claustrophobia kicking in; I could feel the heat from the blistering sun even though the windows were shut and the blinds drawn.

“He doesn’t speak English,” Mourad smiled at me. “What are your questions?”

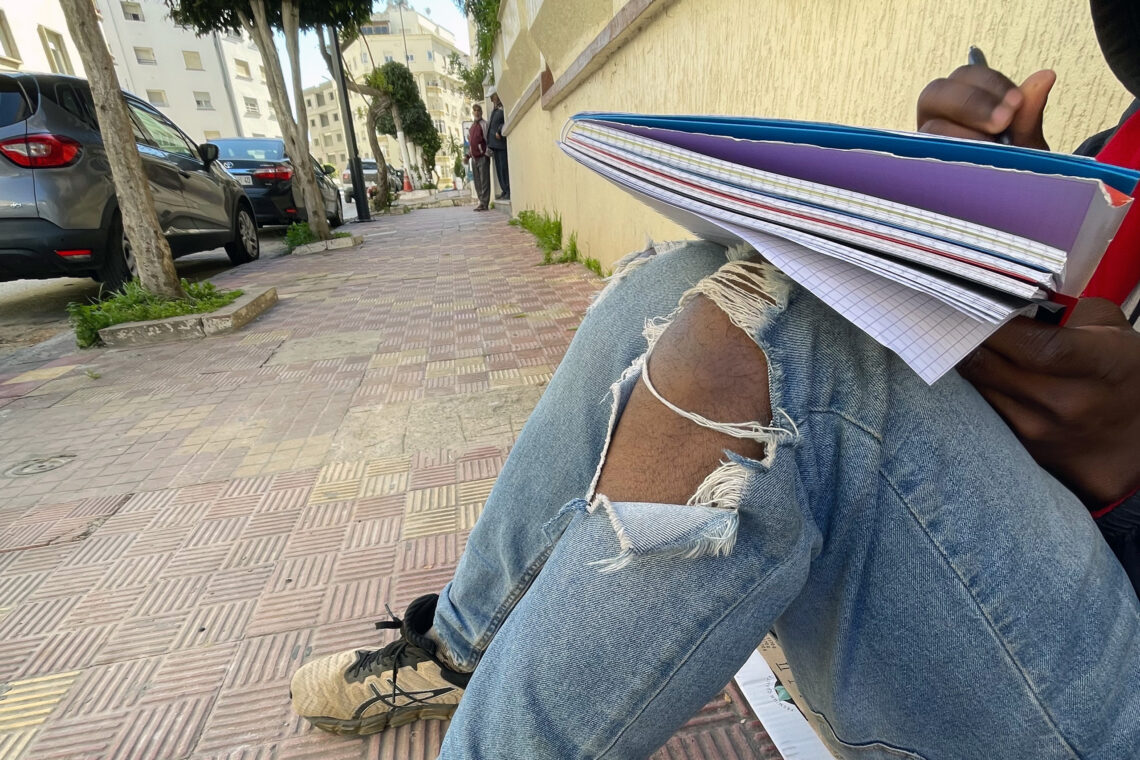

Damn, I thought. I had been thinking of questions throughout the week but never had the chance to write them down. I clung to my notebook, fearful that my knuckles would turn white or that I might drench the paper in sweat from my palms. “I … uh.” It was hard to think. I really should have taken an extra pill before I left.

“What made you get into calligraphy?” I finally asked with a quivering voice.

Mourad and the man talked for a long time, so quickly I couldn’t even catch any of the words I learned in Arabic class. “His origins,” Mourad said after he finished his long conversation. I had no idea what that meant. Wasn’t the whole point of this interview supposed to be about me finding out what his origins were? Was Mourad just not telling me the whole story? The two sat in silence as they both stared at me, waiting for my next question.

I was starting to regret this entire exercise. Now sitting in front of these people, my mind went blank. “Uh, hold on a second,” I mumbled, trying hard to remember what exactly I should be asking. It was then the man whose name I still didn’t know started talking once more. Mourad nodded, laughing from time to time as the conversation continued on in Arabic, the words soaring over my head.

Another man came out from a room of the studio, putting down a kettle and pouring us all some tea. “Shukran,” I mumbled, not trying to disrupt the conversation between Mourad and Mystery Man. I didn’t even like the mint tea; it had far too much sugar for me to handle. But I didn’t want to be rude.

Mourad took a sip of his tea before turning to me, ready to give me information.

“He used to do business before in Marrakech. He’s been in Tangier for five years.”

Mystery Man spoke up once more, Mourad simply nodding.

“Since 2013.”

With Mourad telling me information and MM—now my designation for him—still talking, I couldn’t help but wonder if he understood some English. Once again, the two of them began talking to one another, but at least now I was able to write something down. “MM is married with two daughters and one son, and he was charmed by Tangier. He had to make a choice, Casablanca or Tangier; but he liked Tangier better. Tangier was better for his artistic aspirations.”

A pause in their Arabic conversation gave me more opportunity to write.

“His daughters play violin,” Mourad nodded, seeming more fascinated by this interview than anyone else in the room. “They were brought to Tangier for their lessons, right down the road there.” It was then he explained that MM had fallen in love with this place while sitting on the wall across from his art studio. He sat there staring down at the old port while he waited for his daughters to finish their violin lessons before they drove back to Marrakech, eight hours away. That was a long drive, so he found it best to just move there for his daughter’s sake.

Mourad described one time when MM was sitting on the wall and something happened that made him want to make his art studio.

“What was it?” I asked.

“Kids were shooting themselves and sniffing glue right out there.” The two of them pointed out the door and I turned around to look. I couldn’t help but be a little distracted. I was wondering how kids were going around with guns just casually shooting each other. How did the police not notice the violence? It took a while for me to understand that shooting themselves didn’t mean that the children had guns; it meant that they were doing drugs.

“He wanted to give these kids something else to do. To teach them.” Mourad spoke softly, telling me about how MM called the government and managed to get the use of an abandoned building—the city’s old mortuary—which he turned into an artistic space, a safe place for kids.

I tried to imagine what it must have been like for MM to watch children destroy their lives—and feel the need to do something about it.

“Art is healing,” MM said, and even though I didn’t understand Arabic, I knew there was pride in the man’s voice

Mourad kept talking, and the man that served us tea earlier stepped into the studio once more, taking pictures of us. I tried to focus on the flying words I didn’t understand, nodding every so often. “He has no free time,” continued Mourad, nodding at MM. “He paints at home, too.” Mourad next translated the man’s words: “Painting isn’t for business, it’s about human sharing, and sharing everything is the best thing in life.” Mourad, poking at my pad of paper, said: “Quote that!” He watched me write before giving me another quote from the man: “Art is a sacred message to share and to give.”

At this point, Mystery Man called over to the man taking pictures and barked some orders. The man left for a moment or two before coming back with photos and an essay someone else had written about him. The servant also placed a large slab of rock on the table. After being halfway through this interview, I had finally learned Mystery Man’s name thanks to one of the many pieces of paperwork he placed in front of me: it was Bellali Abdelfattah.

I learned that Mr. Abdelfattah, in looking for artistic inspiration, studied ancient writing, looking for symbols or any means of communications that were engraved on the stone. Those symbols were for him a source of power. At first, he just went to prehistoric archaeological sites to look for the symbols in the ruins, but then he began producing his own art. He was one of the first people in Morocco to hold an art exhibit that integrated ancient symbols into his own calligraphy work, and he was soon dubbed the “Prehistoric Man.”

Abdelfattah drew on the rock he placed on the table, leaving marks from just his finger as he explained how the people from the past would leave their marks. He continued talking about hieroglyphics and their writing style before he changed the subject and described the ancient works as a “silent language.”

The Atlas Mountains, he said, contains petroglyphs from over 5,000 years ago. I don’t remember exactly where Bellali told us that he went, but it’s clear that Morocco is swarming with relics.

While Bellali spoke about his journey to find art, it brought me back to Paris, wandering through the labyrinth that is the Louvre. I admired the Mona Lisa and the Winged Victory of Samothrace. But as symbolic and beautiful as these works were, my attention turned to stones that lined some of the walls. Not just flat stones, though; they were chunks of rock taken out of what was probably a wall and covered with words in Greek. What caught my eye as well were the lines across the stone slab. They were straight as if someone had been writing on lined paper, except there was a trace of lines to be seen.

Calligraphy is something I’ve always known about yet never attempted; I never had an attention span that lasted long enough for me to care for such a thing. The visit to the Louvre reminded how beautiful Greek writing was. The Greeks clearly had to put a lot of attention into what they were writing, for there wouldn’t be any chances to turn back. They didn’t have whiteout to cover up their mistakes for when their hand slipped and they didn’t have a delete button or backspace to get rid of what they may have miswritten. What they were writing was literally written in stone. There wasn’t much one could do to fix those mistakes unless they wanted to start all over once more.

Bellali’s voice snapped me from my daydreaming about the Greeks. He spoke about the different styles of Moroccan calligraphy: Mabsut, a sacred writing just for the Quran; Mugawhar pearl, for manuscripts and letters; and Musnad, for scholarly writing.

I realized I would be late for Arabic class if we didn’t leave soon, so I stood up and shook Bellali’s hand. He then had the man taking pictures take a picture of him, Mourad, and me standing next to each other. Before we could leave, he offered to show us his studio.

“I’d like that,” I said.

The three of us moved towards the door and entered a small room that reminded me of a cave—because it was a cave. With Mourad translating, Bellali said he wanted a cave in his art studio to remind him of the times he traveled to the caves in the Atlas. He needed such inspiration from far-away places. The ceiling was bare rock, the walls were covered in cave paintings. The biggest one was of a cow.

As cool as it was, I started feeling claustrophobic, and thankfully we filtered into yet another room cluttered with art supplies. The next thing I knew, Bellali was holding a black box out to me. It was filled with pieces of wood in different shapes and small enough to hold like a pencil. Picking one out, he forced it into my hand and said something. “A small parting gift,” Mourad translated. It was some sort of bamboo with a hard thread wrapped around the top. My first calligraphy tool, even if I had no idea how to use it.

After I thanked him over and over, we shuffled out of the building and left. Mourad and I started trudging up the hill back out into the heat once again, but most of the stress that I had before left me. The two of us hopped into a taxi and made our way back to school. My eyes were glued onto the window, watching the scenery go by. I felt like I had learned so much, and couldn’t wait to get out my sketchpad and draw. It had been a while since I had actually felt inspired by something.

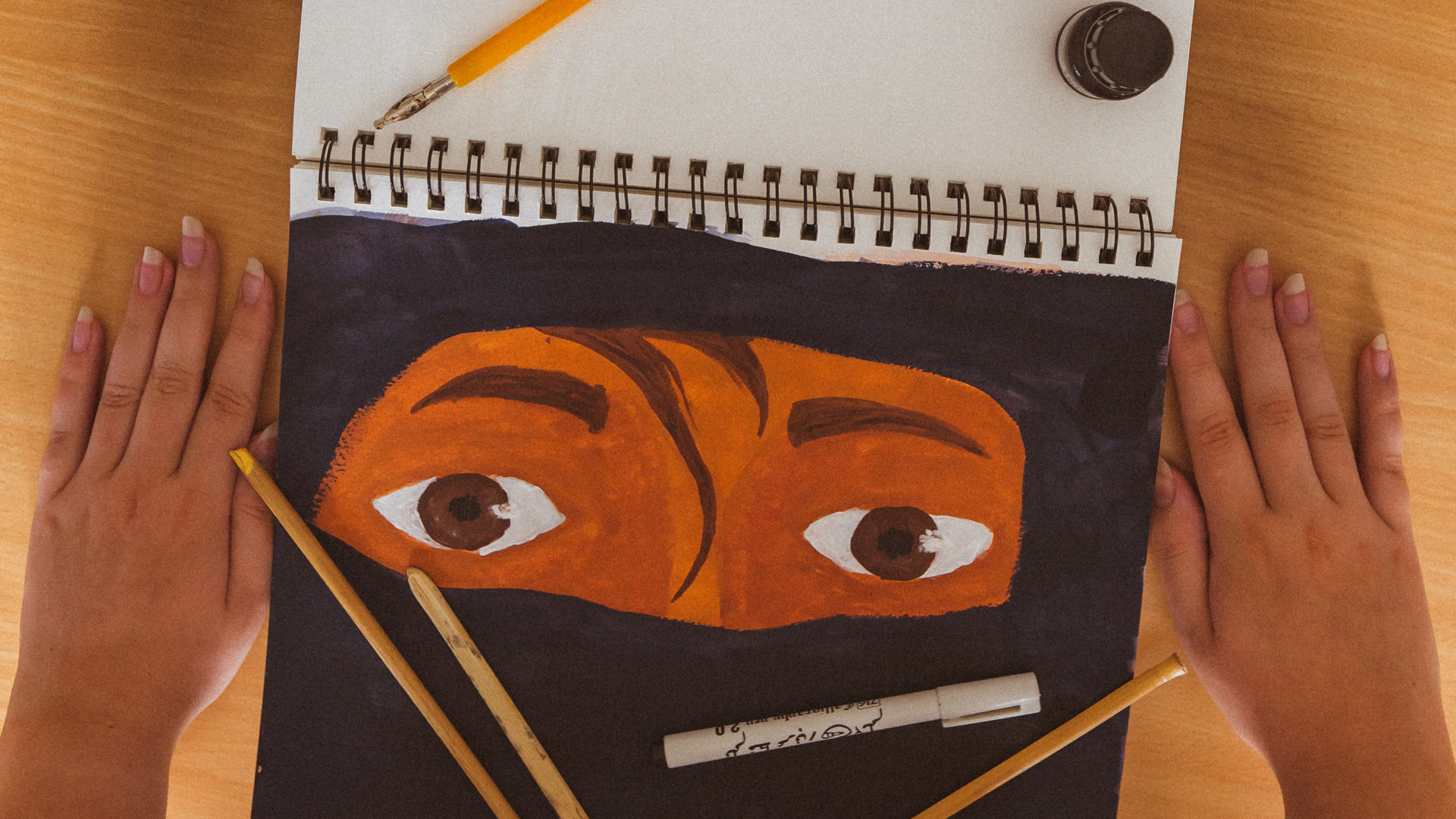

I made my way to my dorm room. My fingers took hold the bamboo piece of wood that my mentor had given me as a parting gift. My eyes studied the fragile creation before looking over to an ink jar. Mr. Bellali created his own form of calligraphy. He changed ancient writing and made it into his own. Could I do the same? Pulling my art notebook out from the desk and flopping it onto the wooden surface before my laptop, I began to fill a blank page with ink.

Comments are moderated by the editor and may not appear on this discussion until they have been reviewed and deemed appropriate for posting. All information collected is handled in a manner consistent with our privacy policy.