“What are those kids doing over there?” I ask as my friends and I walk through the Medina.

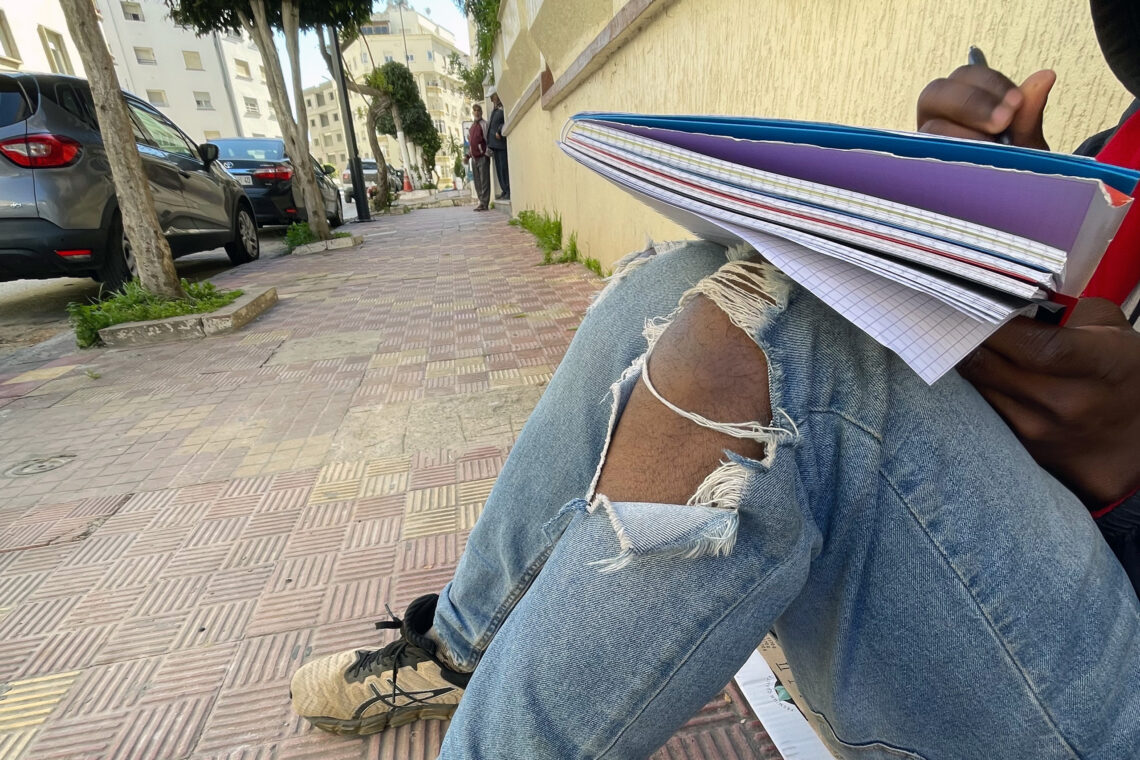

Three young boys were standing together and kept bringing their hands with something on it up to their noses.

“They are sniffing glue,” my friend Maddy says. I stop mid-stride, and my eyes began to water. “Why were kids sniffing glue on the streets, and not in school or playing?”

As soon as I got back from our trip to the Medina, I sat down on my computer and did some research to find some answers. I was not prepared for what I was about to read.

“With a few Dirhams,” I read, “these children can buy drugs. To alleviate the stress of their daily lives they often sniff glue, a cheap and easy-to-obtain drug, or other hallucinogenic substances.”

What if kids had alternative ways of dealing with their pain? Could the future of these children be saved?

This made me think back to my childhood. The fighting in my house never seemed to stop; my parents and sister were always arguing about something. This started when I was really young, and it would always make me anxious and scared. Then, one day, I reached into my bookshelf, pulled out a random book, and opened it up to the first page. The first line read, “‘Help! A monster!’ said Annie.” Instantly, I was hooked. From that day on, the Magic Tree House series became my escape. I would sit down on my bed, turn the volume up on my CD player, and read book after book until I fell asleep. Reading helped me escape reality and by opening the door to a new world of imagination.

Reading, though, was a lot more than blocking out my quarreling family members. It was my passion to search through the bookshelf—since it was twice my size, I’d need to use a chair to reach the top. C.S Lewis got it right when he writes, “we read to know we are not alone.”

I couldn’t put books down, and I didn’t understand how someone could live without the Magic Tree House, the Boxcar Children or Nancy Drew books. How could I save the polar bears in the Arctic with Jack and Annie, help the boxcar children solve a mystery on their cruise, or help Nancy drew find the thief at summer camp if I didn’t bring them with me? Characters like Jack and Annie were my mentors and friends who would bring me on grand adventures. In each novel I read as a kid, I connected myself to the characters and they helped support me in my everyday life.

Thinking about the street kids of Tangier, I wondered if there were people in Morocco trying to use books to help people cope. If I hadn’t discovered books around my home, I never would have explored those rich imaginary worlds. What about Moroccans? While this country is without question one of the most unique and beautiful places I’ve ever been to, one thing has stood out since I arrived in January: I have never seen someone leisurely reading. Libraries seem rare and, unlike back home, people don’t seem to pick up a book when they are bored at a coffee shop. Literacy rates, I’m told, are low here due to lack of proper education.

I decided to do some snooping around the Internet, and an article I found claimed that in the Arab world the “Internet demolishes the good practice of reading.” Is the Internet destroying not only the book culture in Morocco, but also the ancient art of oral storytelling? Is there anyone fighting back?

With such questions in my mind, I decided to pick our campus manager Mourad’s brain. He seems to have an answer for everything.

“Mourad,” I began after taking a seat in front of his desk, “do you think the Internet is deterring people from picking up books in Morocco?” I asked.

His eyes got big as if they were going to bulge of his head. “No.”

Surprised at his answer, I summarized my research. How technology is taking the attention away from the importance of reading and encouraging people to rot their brains using a screen.

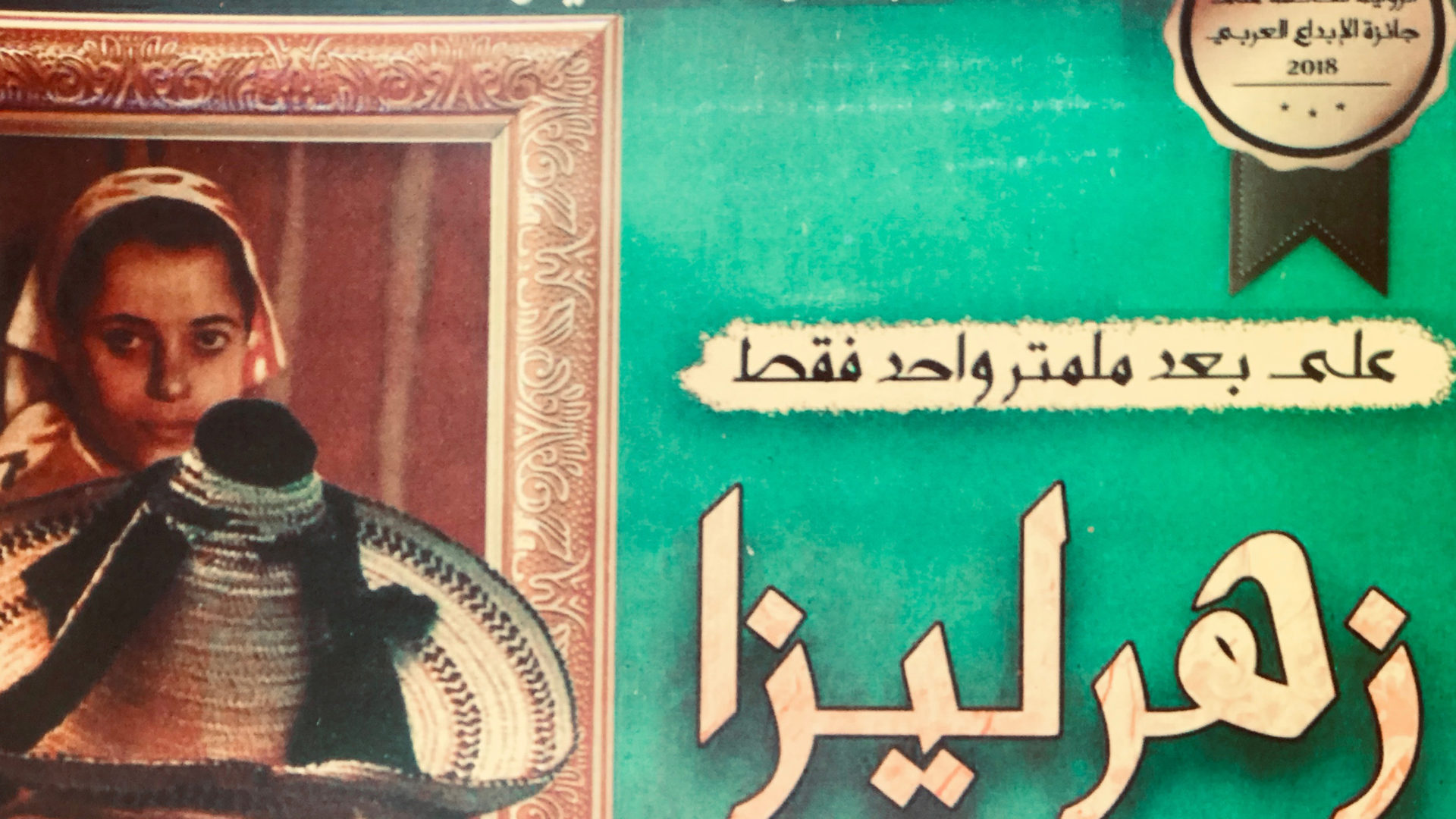

He put down his reading glasses. “Can you imagine a book that is written chapter by chapter with the help of online viewers’ comments and ultimately becomes an award-winning book? Well, let me tell you about an author who is introducing this new form of literacy in the Arab world. In 2013, his book “ZohraLiza” became the first Facebook Arabic Interactive novel that achieved just that.”

What I learned that day from Mourad was this: the novelist Abdelouahid Stitou uses an innovative idea of employing technology to encourage reading and allow greater accessibility. Not only that. His approach to storytelling could even help the poor who don’t have bookshelves in their homes. In the world today, Mourad went on, “technology is available anytime and anywhere.” With easy accessibility, this might be the next step in raising the literacy rates and encouraging people to want to read. Maybe one day street kids will be co-writing books instead of sniffing glue.

Abdelouahid Stitou sounded like a revolutionary. I needed to know more about his style of writing and how he plans to impact the world of reading here in Morocco.

I set my bare feet on the cold tile and sat on the blue couch. I noticed three pictures hanging on the wall across from me, and smelled the aroma of coffee in the air. I noticed these things because my therapist once told me that when I start to feel uneasy and anxious, I need to use my senses to find comfort by “grounding myself.” Anticipating the upcoming interview was making my hands cold and my heart race. I tried to sit patiently in the faculty lounge, waiting for the award-winning author to walk through the door.

“He’s here!” Mourad exclaimed jogging towards the front door of the academic building. I followed him, dragging my feet as I tried to organize my questions and thoughts in my jumbled mind. A bald, medium-sized man stood in the entryway. Instead of wearing a stuffy suit and tie, as I had expected from such an accomplished man, he had on jeans, a gray turtleneck sweater, and a white cardigan. I already liked him.

I picked up my pen with a shaking hand and stuttered out my first question, “Can you tell me a little bit about yourself?”

In a kind of monologue, he rattled off facts about himself. He was born in 1977 and grew up in Tangier. He’s had the dream of becoming a writer ever since he was a child and was obsessed with reading kids’ magazines. With encouragement and support from his family, he was able to carry out that dream. His day job is as an architect, and in every free minute he has he writes his novels and works as a journalist for Hespress, the first online newspaper in Morocco. He also likes to use his published short stories to “reach the younger generation.” To show his success, he recently won the Prize of Arabic Creativity and Thinking in Dubai.

“What inspired you to write?” I asked.

He reached for the mini water bottle on the small table next to us. He glanced quickly at Mourad and back at me.

“Tangier is my inspiration.”

“Why Tangier? Can you tell me more?”

He took a sip of his water. “This place,” he began, “it has always been a part of me. Its beauty and uniqueness inspire me. It is a city with a soul.”

My follow-up question was about Mr. Stitou’s first novel, Zohraliza. His eyes opened wide like he was about to tell me a secret. Zohraliza is about a band of thieves that stole the famous “Zohraliza” painting from the American Legation in the Medina of Tangier. The main character goes on the mission to locate the painting, steal it back, and return it back to its rightful home.

“I’ve heard that you also use technology and social media in writing your books,” I said.

From what Mourad told me, he started on Facebook and later developed an application accessible on mobile devices.

“You don’t read Arabic, right?”

“I wish!”

“Me too. Then you could join the community.”

I had never thought about writing a novel, and the idea I could be a co-writer with people from around the world got my imagination soaring.

“How does it work?”

He explained how he would post the first scene of a story, and with this plot, his readers were given the opportunity to pick which path the characters chose and influence what the outcome would be. In just two months, thirty-five chapters of the novel were written and published.

“In the past, the writer has always been the king, but in my books, I want the readers to have a voice.” Although he actually writes the novel, he incorporates the ideas and suggestions from his readers to encourage and intrigue his viewers to continue reading. His interactive books are designed to allow followers to interact in all steps of the process. With each chapter ending in suspense, it draws the reader in and inspire them to contribute more ideas and anxiously anticipating what is going to happen next. It opens a whole new world of imagination.

On Facebook, he has five thousand followers. He receives emails from individuals all over the world who want to read his book, so he just sends them back a free downloadable pdf version of the book so they too can experience the journey these books provide.

I was puzzled? How could he make money if everything is free?

“So you just give it away?”

I asked. From the open window behind us, I could hear dogs barking and birds chirping in the trees.

“Well, writing is not a profession here, it’s a hobby.”

“Really?”

“Yes, there are only two or three professional writers in the Arab world. You just can’t live off of it.”

“Then why do it?”

“To get a book in people’s hands.”

I could see the passion in Stitou’s eyes. His interactive novels were serving as a way to close the gap in people who read and provide the opportunity to learn and go adventures to all.

“Thank you so much for taking the time to come and talk to me. I think what you are doing is incredible and inspiring,” I said.

I stand up and Stitou reached out his hand and gave me a firm handshake.

“Can we take a picture?” he asks.

“Absolutely.”

He wanted to take a photo so that he could post it on social media to show his interaction with diverse people. After the photos, he pulled out a copy of his book from a bag. He opened it up to the first page and scribbled down some words and handed it to me.

“This is for you,” he said.

“Thank you for spreading the love of reading.”

Mourad walked him out, and I stayed in the room. I picked up the novel feeling the same jolt of electricity I had as a child exploring the bookcase. Although the book was in Arabic, it meant a lot to me that he had helped open my eyes and taught me many things about both Morocco and reading. I imagined what it would have been like for me as a kid, passionate about reading, suggesting ideas and helping to publish the next Magic Tree House. That would have been a dream come true and would have inspired me, even more, to continue reading into my early adult years.

What would happen if the kids I saw on the streets were taught or inspired to read? Maybe they’d find a way off the streets. I just hope that Abdelouahid Stitou’s work and innovative ideas will spread to countries all over the world, especially those with low literacy rates, or where few books are available. I hope that kids who feel so abandoned by society will discover, as I had, that they are not alone.

Comments are moderated by the editor and may not appear on this discussion until they have been reviewed and deemed appropriate for posting. All information collected is handled in a manner consistent with our privacy policy.