“How could anyone let this happen to you?” I thought. So far Moroccans have always been friendly to me. They’ll invite us strangers into the comfort of their home, sit with us on the nicest couch, and make us homemade pizza for no reason. They’ll stop in their tracks and turn around to explain to us what are the best strategies for catching a taxi at rush hour. But then they did this.

We searched for you for a whole week; we had some food and a toy to give you, but you never seemed to be around. We looked around every corner, every street, behind every pile of trash and rubble. I repeated to your other friend Dianne, over and over, that you were tough; you’d lived in the streets since you were tiny, and you’d be fine. But this feeling in my stomach told me you weren’t. Especially on those dark, freezing nights where the wind roared down the narrow streets in Tangier, and the horizontal rain whacked our windows and flooded our rooms, I wondered where you were.

On the night we found you, you were curled up in a corner. You didn’t jump on us like you always do, and you didn’t try to tug on my coat. You barely moved. I could have sworn it wasn’t you, but the little scar on the tip of your left ear told me it was, and so did the way you lay your head on my lap as soon as I kneeled down.

Your eyes wouldn’t open; they were stuck together with pus, and you were hardly breathing. How could anyone let this happen to you? People stopped, smiled for an awkward second, and asked, “Is he okay?” Every time people asked I was filled with indignation. “No, he is not!”

“I know this dog, he’s always around here,” they said. “Well, you should have helped him I wanted to shout.”

One man with a shaggy mustache sat down with us, as we cleaned your eyes and nose.

“Why are you doing this?” he wanted to know.

“Because no one else is,” I answered.

You perked up when you saw we brought food. You gulped it down and took a few steps under the streetlights, showing off your success to all those who were lurking behind the walls, watching the scene unfold. The mustachioed man crouched next to us for a few minutes and watched you with a soft smile.

“Why doesn’t anyone feed him, or give him a blanket to keep him warm?” I asked the man. “No one ever even took him to the vet to get vaccinated.”

The man straightened his back. “We don’t want to touch the dogs. They have illnesses and they’re aggressive. They’re also weird animals; they are always trying to make babies in the street.”

I paused for a second, trying to figure out how a young French woman like me could explain to a middle-aged Moroccan man what neutering is all about.

“The Holy Quran also says dogs are dirty, so we can’t let them into the house,” he added.

I looked at my own hands, black with all the dirt you had in your hair, and showed them to the man. “What if I wash my hands later? Wouldn’t I then be clean?”

He stared at me, his eyebrows frowned, and suddenly they lit up as if struck by an epiphany.

“I get it! I work as a car mechanic, and cars are dirty. My hands get black at the end of the day, and then I just wash them. So it’s not a problem to touch a dog.” He came closer to you, and slowly put his hand out. “Can I pet him?” he asked with a shy voice.

I grinned and nodded. He stroked your head once or twice and gave you a bright smile, as you were smiling back at him.

“This is the first time in my whole life I’m petting a dog,” he said laughing before going on and on about his eight-year-old son Youssef.

“Youssef loves dogs. Every time I come home, he’s watching something about dogs on the computer. Dog movies, dog cartoons, videos of dogs. . . I think he’ll become a vet one day, because he really, really loves dogs. His dream would be to have a dog of his own—imagine if he wakes up tomorrow morning, and there is a dog in his garden! He would be so happy.”

For a second I imagined him taking you to a vet for treatment and then taking you to his home. You’d play with Youssef, who would love and care for you, feed you and make sure you’d never have to sleep out in the rain again. But in my reveries, my eyes met the man’s dreamy gaze, and we both figured out the problem: his wife. She probably wouldn’t approve of her husband’s idea of adopting a sick street dog on the fly and bringing it into the house she spends the day meticulously cleaning.

He thanked us Dianne for helping you and returned to his shop.

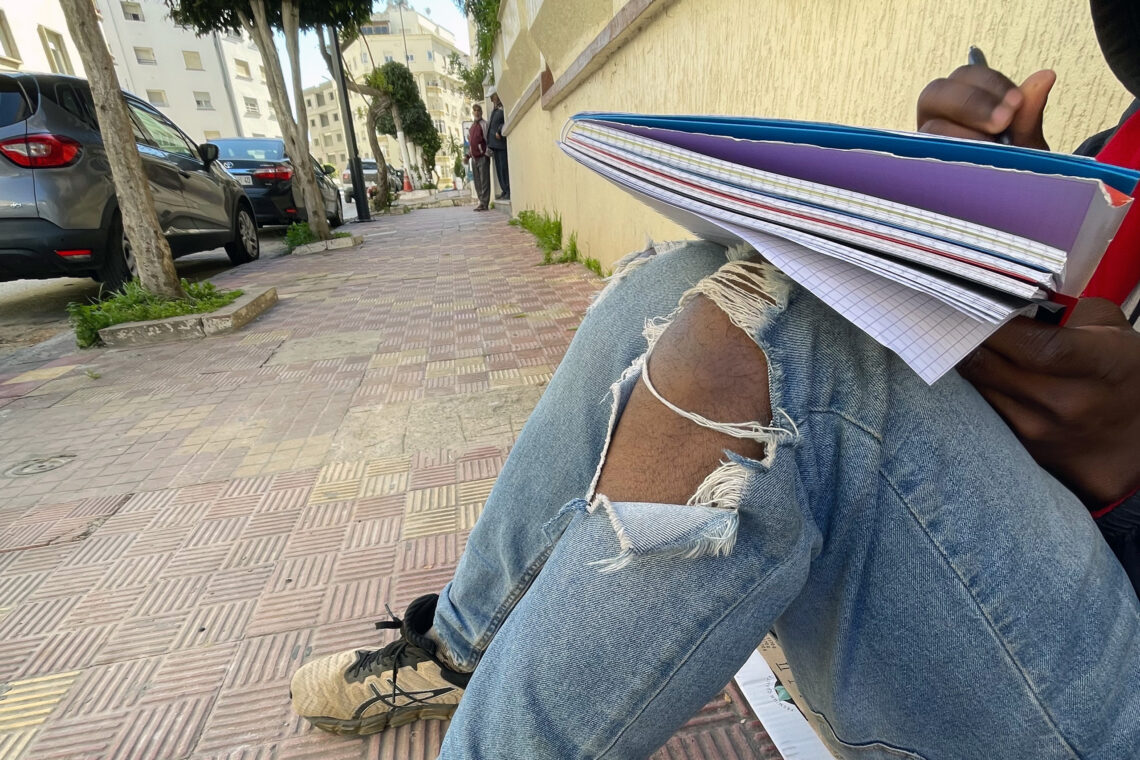

The next morning we found you just a street away, sleeping on a piece of cardboard in the sun, snuggled under a fluffy blanket a homeless man gave you. The homeless man had watched us taking care of you the night before—I spied him staring from behind a wall. A small crowd stopped to ask about you. “How is the dog today?” they asked. One man let his toddler pat your head. Another asked if you needed any food. A kid brought his older sister who was a vet student, and she called her friend who worked at an animal shelter.

It was a funny sight to see. It sounded a little bit like the beginning of a joke: there was a yellow dog, a French woman, an American, and five generations of Moroccans standing at the corner of a street. A day before you were all alone, and today, suddenly, everyone cared. And although you were still sick, I felt so much better. We hadn’t yet changed the world, but it was a good start.

Comments are moderated by the editor and may not appear on this discussion until they have been reviewed and deemed appropriate for posting. All information collected is handled in a manner consistent with our privacy policy.