A soccer ball slammed into my leg as I walked the streets of Tangier. It was my second day in Morocco, and a kid barely eight years old was already showing off his skills. I smiled and passed the ball back to him.

As he ran back to his friends, showing off his foot skills, I thought about being his age, and practicing long balls, one-touch passing, foot skills, and shooting with my father, who loved the game as much as I did. When we weren’t at the field working on my skills, we were sitting on the couch watching La Liga, English Premier League, or Major League Soccer. Like so many young athletes, I dreamed of playing professionally. When I made the team at UNE, it felt like the first step.

The most painful sacrifice I made by studying abroad in Morocco was therefore missing out on the season. Watching the games from across the ocean also made me vow to play soccer in Tangier. I just had to figure how.

One night, I was on my daily run and decided to take a new route from campus. A few minutes into my jog, I passed a soccer stadium and noticed players warming up under the lights. Before I could second guess myself, I ran into the stadium, sprinted over to the players, and asked if anyone could speak English. They just looked at me like I was crazy, so I asked again, this time more slowly. “Does anyone speak English?”

They all turned and looked at a guy about my age wearing a pair of brightly colored Nike cleats. “I do,” he said with a lilt to his voice. “Want to join us? We’re playing pickup soccer against another team! It is 8v8.”

“Are you kidding me?” I replied. “Give me ten minutes!” I sprinted back to campus, stuffed a water bottle and cleats into a bag, and asked my friends Parkers and Ben, also members of the UNE soccer team, to join me. Moments later we were racing helter-skelter back to the field.

When we arrived, Parker was placed on one team, and Ben and me on the other. As I stepped onto the field, I noticed that it was turf, and that unlike at UNE, no one was wearing shin guards or jerseys. The referee handed out pinnies to distinguish the teams.

The match began. Most of the players were very good, pulling out moves such as the “Maradona” and “Scissors.” I ended up passing the ball a lot, not holding onto it for too long, though I did score twice.

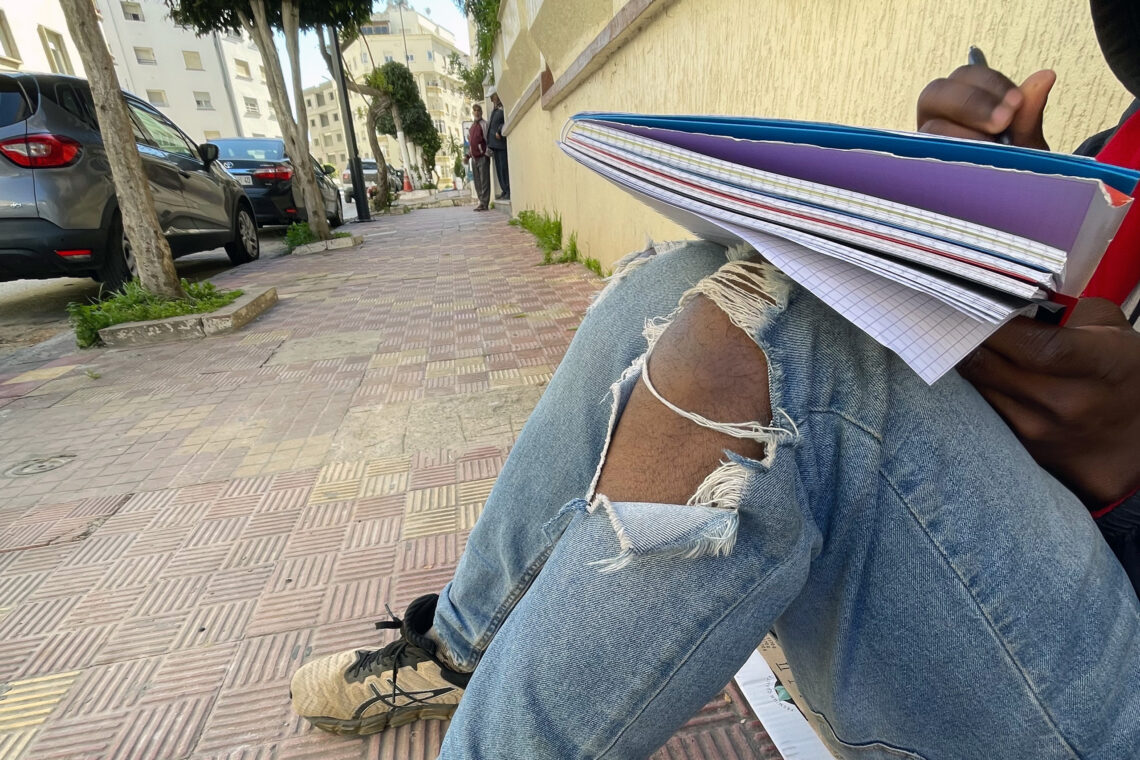

After the game, I approached the player who spoke English and asked if we could chat. I wanted to know everything about his life as a soccer player. He seemed as eager to talk as I was to listen. “I grew up playing soccer like most kids here. It was something everyone watched, everyone played, and everyone loved. Street soccer was what we lived for, and we would use water bottles for goalposts and curbs for sidelines.”

“I always wanted to play professionally,” he added, wiping sweat from his eyes, “and that meant joining a club team and traveling around Morocco for games. But because that costs a lot of money, I decided to study business instead.”

While we took off our equipment, he explained how he and his friends use what they earn from their jobs to rent out fields to play pickup soccer. When I realized that they had rented the field that night, I tried to offer him money, but he wouldn’t take it. Instead, he asked for my number, so he could call me when they played another game.

Several days later, I heard about another soccer stadium within walking distance from campus. Though it was getting dark, at once I tossed my cleats in my bag and headed into a nearby neighborhood. Stray dogs were wandering around the unlit streets. I noticed a group of people walking behind me and started to walk more quickly, until I remembered that Tangier has less violent crime than most cities in the US.

When I arrived at the stadium, I noticed two teams warming up for a match. Once the players started trickling onto the field, I dashed down to a group of players and asked, “Do you need a player? I play soccer for a college in America.”

Everyone seemed confused. “Does anyone speak English?” I asked. They remained puzzled and began speaking to each other in Darija. I had no choice but to pull out my phone and fire up Google Translate.

I translated back and forth with one of the players for several minutes before he nodded, smiled, and said he’d talk to his team and get back to me.

A few minutes later he returned and threw a green jersey with stripes at me. “You’re three.” In soccer jargon, I knew exactly what that meant — I’d be the outside back on the left side. I put on my cleats and jersey, warmed up, and was ready to go.

Looking around at the other players, I realized was the youngest by at least five years. While the stadium wasn’t packed, there were at least 50 people in the stands watching and cheering for us to start. The turf was soft as velvet.

The whistle blew, and the game began. My team played well together, passing the ball with ease and rarely hitting long balls. The players were also very talented on the ball.

I didn’t want to disappoint them, so I charged up and down the flanks using my arms to gesture. Despite their skill, my team couldn’t finish a play for a goal, and the other team’s very good group of strikers scored two goals on us in the first twenty-five minutes. Even though we got scored on, my team remained positive. We’d fight back.

Suddenly, I heard someone yelling in pain on the other side of the field, and everyone started shouting and running toward the player. I thought it was best to keep my distance and wait until the others helped the injured player off the field. Several minutes passed, and I wasn’t sure why the other team hadn’t just sent in a substitute; they had plenty.

I finally walked over and let out a gasp. The player’s ankle was completely snapped. After a couple more minutes, a few players picked him up, carried him out of the arena.

I’d seen plenty of serious injuries in my days. Back home, during my first game freshman year, a teammate fell on his collarbone and broke it. He was carried off by the medic and taken to the hospital. But the game continued like nothing happened. In Tangier, by contrast, everyone began walking around, unsure of what to do. Players finally started taking off their equipment.

I grabbed my phone and used Google Translate to ask someone what was going on. After he handed me back my phone, I read, “Morale is down, we cannot continue.”

My God, I thought. Moroccans really care about each other. In America, the game always goes on, but here even the guys on the opposing team couldn’t imagine playing after such an injury.

As everyone trickled out of the stadium, the same man who told me that morale was down whipped out his phone and translated a message for me: “My name is Bilal. If you would like to play again, give me your WhatsApp.”

Sure enough, a few days later, I received a text from Bilal telling me they were playing on the upcoming Friday. “Can you play?”

I told him I was traveling to France so I couldn’t, but I asked if he wouldn’t mind answering a couple of questions that had been rattling in my mind. I wanted to know about him — how he got into soccer, and how he got so good.

He told me his story, about his mother signing him up for a local team when he was a kid, about competing around Morocco in his teens, and about his dreams — like mine — of going pro.

And like me, reality got in the way. He’s now twenty-seven and works for business firm in Tangier, and he hopes one day to make it as a businessman in Casablanca.

What mostly came through our back-and-forth over our phones was his passion for the Beautiful Game. And playing soccer with locals, seeing them move, and watching them march off the field because of the injury, gave me insight into a beautiful culture. To quote Cristiano Ronaldo, “I learned all about life with a ball at my feet.”

Comments are moderated by the editor and may not appear on this discussion until they have been reviewed and deemed appropriate for posting. All information collected is handled in a manner consistent with our privacy policy.