The kid, no older than thirteen, dressed in torn jeans and a coat smeared with brown stains, stuck his nose in the brown sandwich bag and inhaled the glue fumes, which dulled his hunger pangs. Sniffing glue takes a serious toll on the health of street kids, putting them at serious risk of acute respiratory failure, brain damage, and heart rhythm disturbances.

Sipping on strong Moroccan coffee, I sat there watching him from my cafe table in the sun of Tangier’s Grand Socco. Some of his mannerisms reminded me of kids I work with as a summer camp counselor back in the US. There at the cafe, I decided to talk to some of these streets kids in hopes of hearing their stories. My idea was to give them a chance to share their stories with the world and to show that they, too, are human, no matter how difficult the lives they have had. What follows is that journey.

Today is going to be an important day, I remember thinking as the taxi sped off towards Darna, an organization that helps homeless children.

I sat in the back and silently stared out the window, while Mourad, our campus manager, took the front seat so he could direct the taxi. It was 8:45 in the morning, and even though I hadn’t had any coffee, anticipation kept me on edge. The cab dropped us off at a park, from which we walked the rest of the way to Darna while discussing what to expect from our visit. As we turned the corner, tall pale blue walls came into view. The gate was open, and we strolled in. Mourad greeted the receptionist who told us to wait for Mrs. Alami, the director.

While we waited, we walked over to a makeshift soccer field and sat on a bench. Looking around, I thought to myself, this place does all it can to look like an inviting home. There were colorful murals and a sculpture made of various pieces of scrap metal, and next to it was a little metal gazebo made from thin metal pipes. Two soccer goals lacking nets were at the end of the courtyard.

Suddenly, we were approached by a young man around my age—nineteen. He spoke in French to Mourad, who translated for me. The man, who asked us for privacy’s sake to call him “K,” said he’d been coming to Darna for many years, and that he’d heard I was there to listen and document the stories of some of the kids. He told me that the kids come from all over. In some cases, their parents simply abandoned them; others ran away from home to escape sexual or physical abuse. Some are from migrant families with parents who have been deported, fallen ill, or died, leaving the children to fend for themselves. Most of the kids have been on their own for a while. To travel, they hide in trucks on the inside of the tires or hide in the truck’s utility toolbox on the side, then close themselves in it and breathe through a straw. He said many of them, unfortunately, die trying to smuggle themselves on these trucks behind tires where they get crushed. “It’s horrifying but true,” said K.

I saw a lady coming down the passageway at a brisk pace holding an iPhone. This must be her, I thought. I thanked K for his time and turned to greet this woman in a dark blue dress and a thick coat of red lipstick. She smiled and extended a hand introducing herself to us. “You must be Jack.”

“Yes, that would be me.” I returned her handshake.

“Let’s get down to business. You can come anytime you want to help out and talk to the kids. But you may have to come many times for them to open up to you. They won’t trust you at first. I also won’t be there to hold your hand and translate. You will be on your own.”

She walked away, leaving me standing there, mouth agape, my head spinning. This was no summer camp.

Determined to find a story, a few days later I climbed back into a cab. Returning to Darna alone made me nervous. In Tangier, it’s hard to hide that I am an outsider, a symbol of wealth in a city of cracked walls and curious stares. But I can’t help it that I scream American to those who look at me.

I stepped out of the cab and strode through the open gates only to find the main office empty. I wandered into the main building where a group of girls was sitting around a table doing some writing exercises with two women who I assumed to be teachers. I was eyed by all the students.

“Jack?” asked one of the teachers, breaking the silence.

“Hello, I’m here with permission from Mrs. Alami.”

She got up with a smile and told me to follow her to the office where she made a quick phone call. Five minutes later, a fifteen-year-old girl named Fatima came down the stairs.

“Hello Jack, Mrs. Alami told me you were coming. I can translate for you, but I don’t have long. I have duties that I must attend to soon. I also can’t promise any of the kids will talk to you.”

“Thank you,” I replied. “Do you have an idea of a kid who is the most willing to share their story?”

“We shall see. Some of them are very shy.”

Fatima led me back into the main building. Upon re-entering, I admired the walls covered with artwork created by the kids depicting happiness and peace. Bookshelves lined the walls. Clearly, Darna wanted to do everything it could to spread a life-affirming spirit to the kids.

Fatima said something in Arabic to the group of kids and a few of them responded back. She kneeled next to a young girl with long locks of curly black hair.

“This is Mira. She will answer some of your questions.”

Crouching next to her, I learned that Mira is twelve years old. She’s fairly new to Darna as she’s been staying there for the past two weeks. She was born in Tangier and has lived here all her life. I asked her where she was before coming to Darna. “I have no mother. She died a few years ago. I was with my father, but he didn’t want me. I was living in the street when Darna found me.” She told me she used to be super skinny as she never got enough to eat, but Darna has gotten her back to a good weight.

“Tell me about what you do here.”

“I learn mostly. They teach me writing and reading. I like to paint, too,” she said, gesturing to a painting of hers on the adjacent wall. “I want to learn to work with wood, but they say I am too young. I also sew.”

“What would you like to do when you are older?” I asked.

She smiled and looked up to Fatima. “A nurse. I want to help people who are sick. Lots of people have helped me when I was sick, and I want to do the same for others.”

Here was a child with real ambition, I thought to myself, smiling in admiration. The world knocked her down but here she is, trying her best to defy the odds. Hearing Mira speak with such confidence made me think of the kids on glue I’ve seen milling around the Grand Socco. What about the kids that fall through the cracks?

The following day, a Friday, I walked from campus to Grand Socco. Men holding prayer rugs filed out of the mosque into the square. Less pious men sat sipped mint tea in front of Cinema Rif, while vendors hawked their wares and restaurant owners brandished their menus at passing tourists.

I had arranged to meet Saiid, a man who sells knockoff sunglasses on my professor’s doorstep, who had offered to translate for me while I interviewed some kids from the street. He told me he knew exactly where to find them as they frequently pass his sunglass stand.

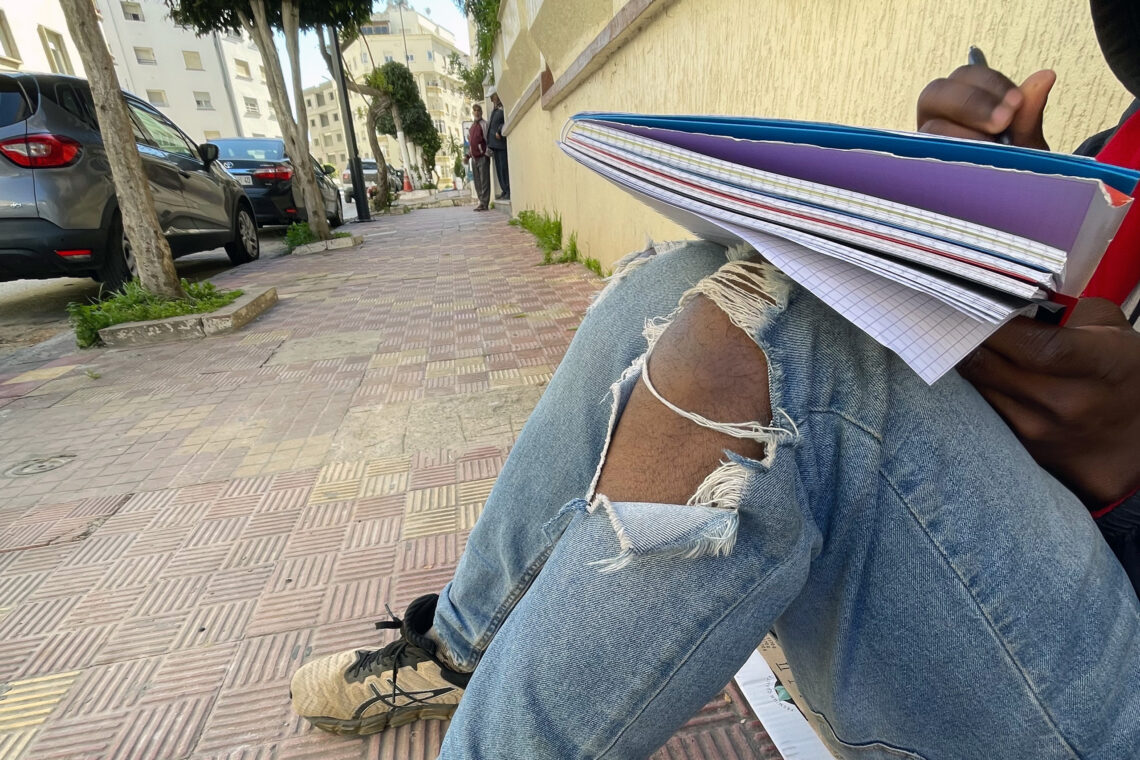

Saiid greeted me with a kiss on both cheeks. Within thirty seconds, he’d spotted someone and strode straight up to a kid I wouldn’t have guessed was homeless, a dark-skinned boy wearing a heavy coat and baseball cap. From across the street, he appeared to be a normal teenager, but upon closer inspection, I noticed greasy hair under his cap and spots of dirt on his coat and jeans, which had holes in them, and a glue rag sticking out of one of the pockets. With meek eyes, he stared at my fresh haircut, clean jeans, nice flannel, overpriced jacket, and the iPhone in my hand. We locked eyes and knew we were worlds apart. I saw envy in his eyes, and I fought off a sense of shame. I told Saiid to tell him we would buy him a meal if he answered some questions about his life. With a sly smile, the kid nodded.

In short order, I got the basics. His name is Nazeem and he’s seventeen. He lives just down the road under an awning and sleeps on a flattened cardboard box. He was born is Ksar el Kebir but moved here a few years ago with his family. “What is your family situation,” I asked. He looked down at the pavement. “My mother is very sick. She has a heart issue. I have no money to help her, which is why I come here to beg.”

“Why not get a job and raise money for her?”

“Finding a job here is very hard. Nobody wants to hire a homeless boy. I believe I would be a good worker. My father always told me that.” With that, he looked me in the eye again and said, “But my father is dead now. I am the youngest of my siblings. They do their best to earn money, but I am often on my own.”

I told Saiid to tell him I am asking these questions so that I may share his story. That I wanted to bring awareness to kids like him who are struggling to get by in Tangier. Nazeem responded with a “thank you” and a smile. Then he told me he is occasionally helped by foreign organizations. Every week or two, a Spanish organization comes to feed him and make sure he is healthy. He wishes they would come more often.

“What do you do every day?”

“I come to the Grand Socco and the Medina and I beg or try to find work. When I get enough, I take a bus to my mother and give her the money, then I come back here. I have been living on the street for two years.”

I nodded along, barely processing his ordeal. He’s only two years younger than me, and yet he has to fight to survive in ways I can’t fathom. He cares for his mother when no one else will. He has ambitions and dreams, but he’s caught in a tragic loop: too poor to get off the street but unable to get a job because he lives on the street.

I learned more about him. How he’d like to cross over the Strait and escape to Spain. Or how he’d love to return to school and how he dreams of curing his mother. He loves soccer and would like to study business.

I gave him the equivalent of three dollars, enough for a meal, and thanked him for his time. His face lit up. He shook my hand and walked off with a grin. Those thirty dirhams may have been more money than he receives on any given day.

“Come this way,” Saiid said, “I’ll introduce you to some more of these guys.” We walked down to the Mohammed VI Avenue, a four-lane street that stretches along the port. We turned the corner and start walking towards a big grassy hill with trees. Under one tree was a boy of around thirteen.

Saiid whistled at him, and the kid cautiously got up as we walk towards him. He was wearing black jeans with a big gash in the right pant leg. Like Nazeem, he obviously hadn’t had a proper bath in days. His face had a light coat of dirt, and his teeth were a pale yellow. Before we opened our mouths, he put his hands to his, motioning for food.

Saiid introduced both of us and told him we would give him money for food if he answered some questions about himself. Nodding, he sat on the ground and looked up at me. For some reason, he reminded me of my little brother. His big eyes stared straight up at me with wonder, like he wanted to trade places. Like he wanted to be the lucky one for once in his life.

Saiid spoke with him in Arabic, and after a few minutes Saiid summarized for me: “His name is Youssef and he is 13 years old. He is from Sale, close to Rabat. After both of his parents died, he used whatever money he had and bought a bus ticket to Tangier. He came to Tangier because he wishes to cross to Spain, but he lacks all the necessary paperwork. Everyone he knows wants to leave the streets and go somewhere else. He has been here in Tangier living on the street for two months. He has never had schooling and is unable to get a job. He sleeps on this hill under whatever tree is unoccupied.”

I couldn’t believe what Saiid just told me. “You mean there are so many homeless people here that sometimes he can’t claim his own tree?”

“That’s right.”

“Is he receiving care from an organization that helps the homeless?” Saiid translated to Yussef. “Yes,” Youssef replied. “Sometimes we get a meal or shelter for a few nights. Sometimes these ladies come and bathe us, bring us to a shower to get cleaned up. They will check our health and send us back to the street.” He also told me some of the locals will give him bread or a small meal.

I asked him when he had eaten last. “Yesterday morning,” he responded, gesturing again to his mouth for food.

Suddenly another boy sat next to him and started listening in. He looked up at me curiously and I noticed how young he was. With a flurry of Arabic, Saiid found out his story. His name was Mohamed and he was eight. He and Youssef were brothers. Mohamed wanted to go to school and one day become a police officer. He liked to play soccer when he was able to find a ball.

Intrigued by his ambition to become a cop, I asked him why.

“I want to help people get away from bad people. I also like police cars!”

A third kid joined our group: Omar, age ten, the cousin of Yussewf and Mohammed. His mother was very ill, and his father was dead. He wanted to be a professional soccer player one day, and he practiced with Mohammed.

After explaining that I want to tell their stories, I asked Omar what he would like me to tell people about their lives.

From the way he blinked, I could tell no one had ever asked him such a question. “Every day we all have to beg for money on the street. I hate sleeping outside because nights are cold. I shiver a lot during the night. We all want to get away from here. I want to go to school.”

I pull out a 100-dirham bill—ten dollars—and asked them to share it and get a hot meal. Their eyes widened, and Youssef took the bill from my hand as if I were holding a fistful of emeralds. All three of them burst into laughter, grabbing my hand and pressing their cheeks into it. I thanked them for their time and watched them run off, full of grins, to the closest restaurant.

These are just kids, I thought. They have passions and ambitions, potential and dreams, just like the rest of us. They want to learn and experience what life is all about. They are desperate for a chance to show the world their worth. They are just unlucky. Never have I felt so privileged—so blessed by dumb luck. I did as little to merit my upper-middle-class New Jersey family as they did to end up under trees in Tangier.

Leaving the hill, I headed back to campus, cutting through the American school where I volunteer every Tuesday helping third graders with their writing and reading. The kids who attend this private school are fortunate enough to have parents who can afford for their kids to go there.

Nazeem, Omar, Youssef, and Mohammed are only four amongst the many homeless children in Tangier. They will come up to you and ask for food knowing that most of the time they will be shooed away or ignored. But each one is a person. The second you show them some form of care, they light up with a smile that is so full of potential and life, personalities and dreams and aspirations. They just need care and attention. Of course, you can’t give all your money away to buy them all a hot meal. But a small act of kindness goes a long way. The smile they’ll give you will make it all worth it.

Comments are moderated by the editor and may not appear on this discussion until they have been reviewed and deemed appropriate for posting. All information collected is handled in a manner consistent with our privacy policy.